Since 2012, members of Opera Feroce have been frequent guest lectures giving classroom demonstrations in the Music Humanities department of New York's Columbia University on the topics of Baroque music and opera. Additionally, in the Fall of 2013 we created a pedagogical version of Amor & Psyche: consisting of a live performance with an accompanying Powerpoint presentation. See below for more details.

Classroom Presentation

Our classroom presentation are a fun and informal mix of lecture and performance. Individually tailored to the specific needs of the class and the interest of the instructor. They vary in length from a 10-minute baroque overview to and entire class period.

+ Sample Program

Lamento di tre amanti (terzetto) Antonio Lotti (1667 – 1740) from Duetti, Terzetti, e Madrigali a Piu voci, Venice 1705

Furibondo spira il vento (aria) G. F. Handel (1685 – 1759) from the opera Rinaldo (G. Rossi & A. Hill, after Tasso), London 1711

Si me la pagherai (duetto) Nicola Porpora (1686 – 1768) from the opera Agrippina (M. Giuvo), Naples 1708

Su la destra (duetto) Nicola Porpora (1686 – 1768) from the opera Agrippina (M. Giuvo), Naples 1708

Si ridi ... E di Costei ... Vincerò (scene) Giovanni Bononcini (1670-1747) from the oratorio La Maddalena a'piedi di Cristo (L. Forni), Modena, Lent 1690

Toss not my soul (lute song) John Dowland (1563 – 1626) Second Book of Songs or Ayres, 1600

Zefiro torna Claudio Monteverdi (1567 – 1643) (Ottavio Rinuccini), from Scherzi musicali cioè arie et madrigali, Venice, 1632

Gran follia di Pittor Nicolò Fontei (d. 1647 or later)

AMOR & PSYCHE

(pedagogically enhanced version)

Our pasticcio Amor & Psyche is performed in its entirety with the addition of a fun and information-packed slide show which runs concurrently with the live performance, creating a living textbook. The slides cover everything from Baroque performance practices, musical terms, and cultural footnotes to facts about the composers and the voices and instruments. The presentation is copiously illustrated with baroque art depictions to amplify the plot and the educational material and instructs on multiple levels simultaneously. Developed for the Music Humanities course at Columbia University.

Forces for Educational Amor & Psyche:

- 3 singers (Amor, Psyche, and Everyone Else)

- 3-piece ensemble

- 1 projectionist

- projector and screen

Running time:

- 63 minutes

- intermission optional

+ listening guide

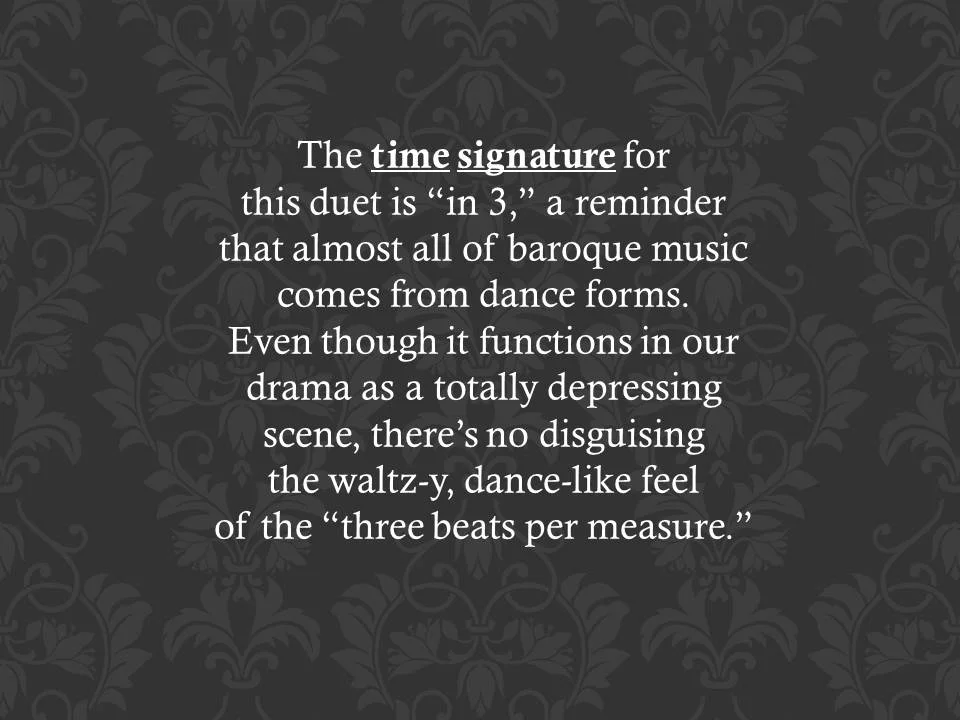

Introduction (instrumental with added commentary) Nicola Porpora (1686 – 1768) from the cantata “Odi qual fasto” Lamento di tre amanti (terzetto) Antonio Lotti (1667 – 1740) from “Duetti, Terzetti, e Madrigali a Piu voci”- Venice 1705 This trio is not from an opera, but hails from a book of secular part songs and madrigals for multiple voices. Like much Baroque music, it is “in 3” (3 beats to the measure) and a good example of the widespread practice of setting popular dance forms as vocal music.

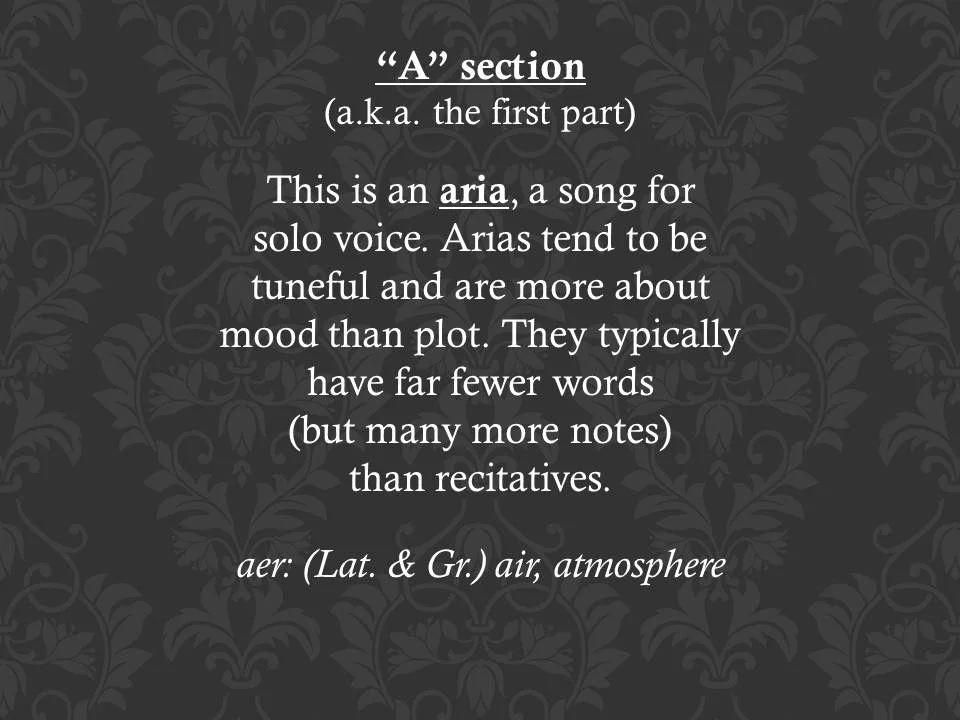

La Farfalletta (aria – Psyche) Francesco Mancini (1672 – 1737) from the cantata “La Farfaletta” Psyche means “butterfly” in Greek and, when we were looking for butterfly arias for Psyche to sing, we found no shortage of material. Comparing languishing lovers to moths happily burning themselves to death was apparently a favorite theme in the 17th and 18th centuries. This aria, or solo song, begins with a section called a “recitative.” Recitatives tend to be much wordier than the aria or song proper, with the rhythm of the sung line closely resembling ordinary speech. Generally, this is the “moving right along” part which serves to advance the plot.

Fire, Fire (song – Venus) Thomas Campion (1567 – 1620) from “The Third Booke of Ayres” London 1617

Furibondo spira il vento (aria – Venus) G. F. Handel (1685 – 1759) from the opera “Rinaldo”- London 1711 This is a “coloratura” aria. Venus’ anger is represented by lots and lots of fast-moving notes, coloring her text and giving a heightened sense of her emotion.

Volarò, ferirò (aria – Amor) Alessandro Stradella (1639 – 1682) from the cantata morale “Otia si tollas periere Cupidinis arcus”- Genova 1680 A very interesting feature of this continuo aria (that is, consisting of only a bass line and a vocal line with no other orchestration) is the distinctive raucous, repeating character of the bass. It catches the ear and makes for an excellent exercise in “listening down” to the bottom of the music. The restless, erratic nature of Amor’s character is easy to hear in the fluctuating harmonies.

All’armi (fragment - terzetto) Stradella (ibid.)

Son vinto... Così va (duetto – Amor & Venus) Stradella (ibid.) Listen for the irregularity in harmony and vocal patterns, particularly in the duet between Amor and Venus. Stradella seems to have been endlessly inventive, and the lack of exact sequences or repeated patterns makes his music fun to listen to (but hard to memorize). Incidentally, he met his end at the hand of a hired assassin. One has to wonder if it wasn’t some singer…

O Grief (song – Psyche’s Father) John Coprario ( c. 1570 – 1626) from “Songs of Mourning”- London 1613

Son nato a sospirar (duetto – Psyche & father) Handel from the opera “Giulio Cesare”- London 1724

Lady if you so spite me (song – Amor) John Dowland (1563 – 1626) from “A Musicall Banquet” 1610

Dormono l’aure estive (duetto – Amor & Psyche) Francesco Durante (1684 – 1755) This duet was actually written as a composition exercise. Durante was an acknowledged master of chromaticism (movement by half-steps), and here he relies heavily on the device of moving back and forth between close intervals to color the text, creating a beautiful weeping effect.

Guerra, Guerra (fragment – terzetto) Stradella (“Otia...Cupidinis arcus” again)

Daphne was not so chaste (song – Psyche’s sister) Dowland from “The Third and Last Booke of Songs or Aires” London 1602/03

Gelosia (duetto – Psyche & sister) Pietro Soresina (18th century) The composers Pietro Soresina and Giuseppe Savatelli who are highlighted in this section of Amor & Psyche are as completely obscure as Georg Frideric Handel and John Dowland are renowned. Beth found this duet and the following aria by Savatelli in the dark corners of a Neapolitan online music library.

Toss not my soul (song – Psyche) Dowland

from “The Second Booke of Songs or Ayres” London 1600

Farfalletta semplicetta (aria – Psyche) Giuseppe Savatelli (18th century)

from the cantata “Farfalletta semplicetta” (manuscript)

The trill is an important ornament created by rapidly alternating between two notes which are close together in pitch. It is used to great effect as a “text painting” device in this aria about a butterfly (what else?) which flies haplessly into a candle flame. The trills represent the fluttering of the butterfly’s wings and the flickering candle flame. For our purposes of characterization, they also effectively create a sense of Psyche’s nervousness.

Fuggi, parti (fragment – terzetto) Stradella (still from “Otia...arcus”)

Farfalletta semplicetta (continued) Savatelli

Der Rheinische Wein tanzt gar zu fein (song – Pan) Adam Krieger (1634 – 1666) Instrumental “ritornelli” or repeated refrains between the verses figure prominently in this strophic song. Incidentally, these two German composers, although both named Krieger, are not known to be related to each other.

Coridon in Geldnöten (song – Pan) Johann Philipp Krieger (1649 – 1725) from the opera “Flora” This piece is actually an aria from a German-language opera composed in the early 1700’s. Notice how vastly different it sounds from the Italian operatic music you’ve been hearing, written in the same period.

Idolo del mio core (aria – Amor) Porpora ffrom the cantata “Idolo del mio core”

Love stood amazed (song – Jove) Dowland from “The Third and Last Booke of Songs or Aires”- London 1602/03

Amor nel tuo penar (aria – Jove) Handel from the opera “Flavio”- London 1723 Baroque music tends to steer away from dark, dissonant-sounding keys like the B-flat minor used here. Handel is undoubtedly creating a special musical effect, which is why we chose this piece to evoke the mystery of Jove’s temple.

Awake sweet Love (song – Amor) Dowland from “The First Booke of Songes or Ayres”- London 1597 In another nod to dance forms, Dowland based this lute song on the Galliard, an athletic Renaissance dance with an irregular rhythm known as “cinque passi” or “cinq pas” (five steps). Listen for the slightly lurching quality of the melody and accompaniment.

Caro, cara (duetto – Amor & Psyche) Handel from the opera “Atalanta”- London 1736 Here is a duet featuring two high voices singing in essentially the same range. The part sung here by Amor was composed by Handel for a famous castrato with an extended upper vocal register. The crossing of the voices highlights the romantic connection between the characters (and perhaps the rivalry between the singers).

Away with you self-loving lads (song – Jove, Venus & Pan) Dowland from “The First Booke of Songes or Ayres” 1597

Laughing Chorus (terzetto) Handel from the oratorio “L’Allegro, il Pensieroso ed il Moderato”- London 1740

+ Program Notes

What’s Baroque? The name baroque is derived from the Portuguese word “barroco” which means a rough or imperfect pearl. It was a somewhat derogatory term applied by 19th century critics to the art of the 17th and 18th centuries which, by their standards, seemed overly ornamented and lop-sided. In European music, it refers to the period from approximately 1600 to 1750.

Mythological subjects in music and art were all the rage in the 17th and 18th centuries, thanks to The Age of Enlightenment’s obsession with Antiquity. The myth of Cupid and Psyche first appears in the Roman poet Lucius Apuleius’ 2nd century masterpiece, The Golden Ass.

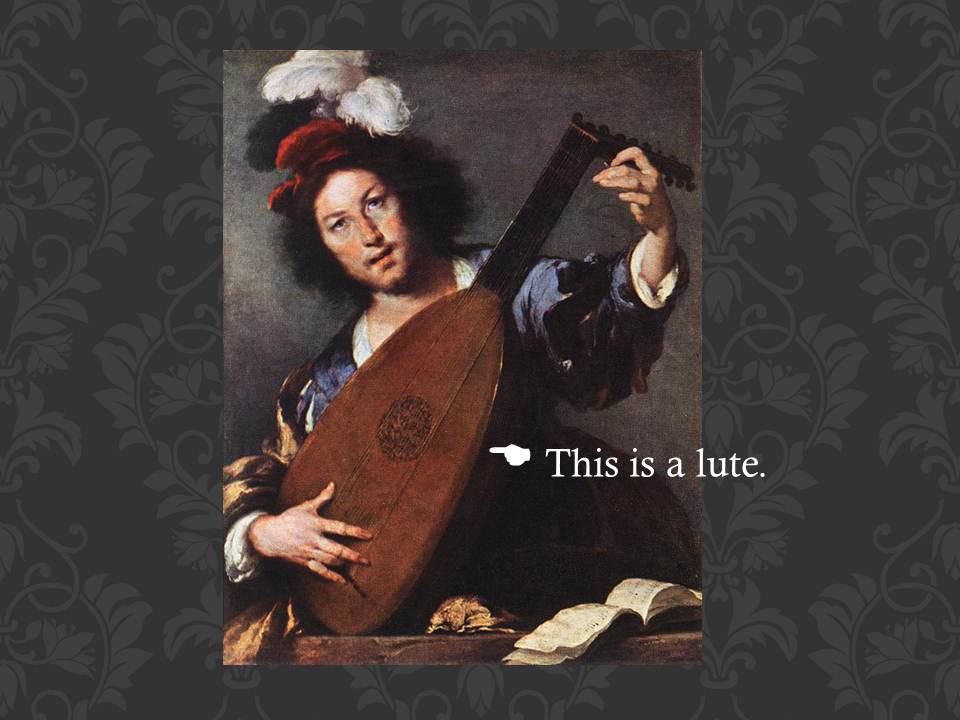

The musical selections included in our pasticcio opera span about 150 years of music history. (Pasticcio stems from the Italian word for pastry, but with the connotation that everything is included but the kitchen sink.) They are taken from a variety of sources: 1) fully-orchestrated operas (typically the pieces in Amor & Psyche which include violin); 2) cantatas (shorter un-staged compositions for one or more singers) and other secular oeuvres (including a composition exercise book!) These include most of the numbers accompanied by continuo only. 3) English-language lute songs which, not having a lutenist in the band, we arranged for our instrumental forces. (The lute is a precursor to the modern guitar and had its hey-day in the Renaissance and Early Baroque.) The lute songs in Amor & Psyche are the oldest works in the show. Composed in England during the early seventeenth century, they coincide with the period when the very first operas were being presented in Venice.

One of the principle musical forms used in baroque composition is the da capo or A-B-A form. The basic melody is heard in the first “A section.” Then a shorter, contrasting “B section” (frequently in another key and with a completely different rhythmic feel) is sandwiched between the first A and the da capo (literally, “from the top”). In the da capo, all or part of the A is repeated, but with variations on the original melody called “ornamentation.” There are several examples of da capo form in Amor & Psyche, with the most complete being “Amor nel tuo penar,” the Italian aria sung by the character Jove. The scene itself is quite static and the focus is squarely on Handel’s haunting melody, beautifully ornamented by Alan in the repeat.

You may also notice that many of the selections have a very dance-like feel. This is not a coincidence. Vocal songs, arias, duets, etc. grew directly out of the rhythmic structure of the dance forms: gavottes, gigues, minuets, allemandes et al. which were all the rage in the ballroom.

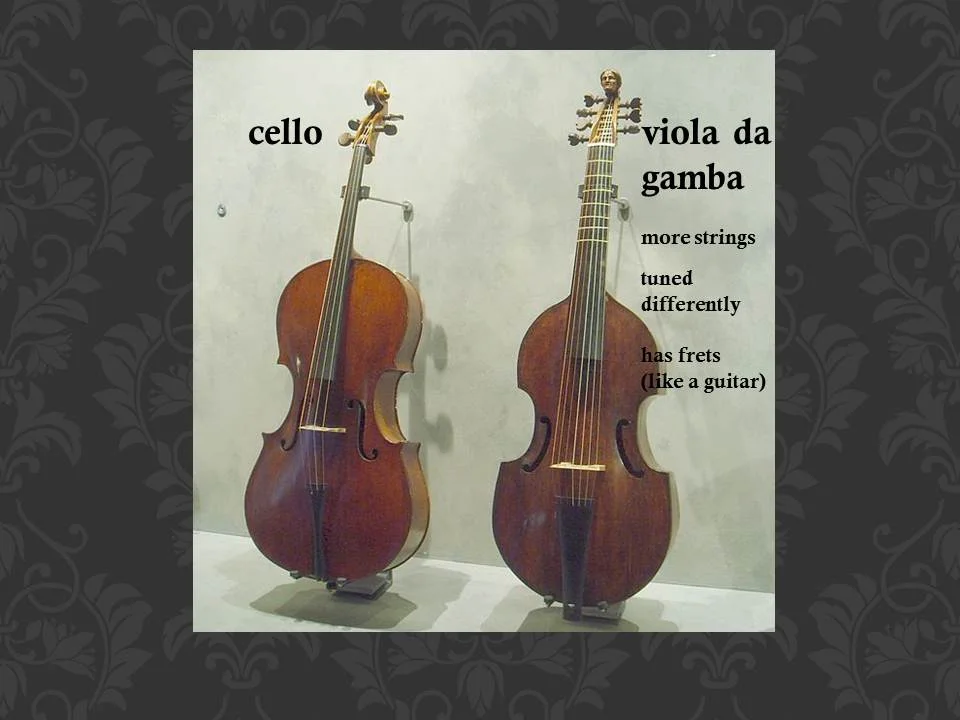

The mainstay of Baroque instrumentation is the continuo section which is usually comprised of harpsichord and a bowed instrument; in our case, viola da gamba. Continuo means “continuous” and the continuo players are responsible for fleshing out the composer’s bass line, the ground of the piece from which the rest of the music springs. Motomi and her viola da gamba keep us firmly rooted in the rhythm and harmony by playing the bass as it appears in the manuscript. Kelly, on harpsichord, has the same single-note-at-a-time bass line in her part, but her job is to quickly analyze the harmony and fill in the texture with chords.

The harpsichord differs from the modern pianoforte in several ways. Its strings are plucked with plectra made of bird quills (or on many modern instruments, plastic), whereas the strings of a piano are struck with hammers. There are no pedals on the harpsichord, therefore it does not sustain or play at different volumes. Textural differences are achieved by playing more or fewer notes or by rhythmic variations. Harpsichordists are similar to modern-day jazz musicians; they are on-the-spot arrangers and rarely play a piece of music exactly the same way twice.

The viola da gamba looks like a lot like a ‘cello, but is a completely different breed of instrument. It is tuned differently, has frets (like a guitar), has more strings, and the bow is held “upside down” compared to that of a ‘cello.

Vita’s baroque violin is a historical instrument dating from 1706, which means it was already alive when much of the music we are performing was being composed! Basic differences between a baroque and modern violin are the lack of chin rest and the use of animal gut strings (baroque instruments are definitely not vegan!) as opposed to the brighter sounding metal strings used on modern instruments. All in all, the general “feel” of baroque music is considerably more intimate than most of the operatic and instrumental music written in later periods. Nowhere is this reflected more than in the mellower sound aesthetic for the instruments.

The three voices you will hear are: soprano (Beth/Psyche), the highest female voice; mezzo-soprano (Hayden/Amor), literally middle soprano, a slightly lower range and darker sound; and countertenor (Alan/Venus, Psyche’s Father, Psyche’s Sister, Pan, Jove). Countertenors sing in the male falsetto or “head voice” and (along with mezzo-sopranos dressed as boys), have adopted much of the music originally composed for the castrato singers (yes, that’s what you think it is) who were the rock stars of the Baroque era. The practice of castrating young male singers to keep their voices from changing dates from the mid-sixteenth century. Females were not allowed to sing in church and, as liturgical music became more sophisticated, it took the boy trebles longer to master its complexities. Some genius had the bright idea to neuter the best boy singers and thus alleviate the necessity of constantly having to train new sopranos and altos.

On the topic of gender, the theater has always been a fertile ground for gender crossing. Before the Restoration era of English theater in the mid-1600’s, women were banned from the stage, and all parts were played by men and boys. We have already mentioned the church’s ban on female singers but, especially in Rome, women were frequently not allowed on the opera stage either, necessitating the female roles to be sung by castrati. In the early nineteenth century, the popularity of castrato singers began to wane, but the taste for sweet-voiced heroes continued. By this time, all bans for women in the theater had been lifted and female singers began to take on the male treble roles. Composing music for male characters to be sung by women en travesti became a very popular device in 19th-century Italian bel canto opera and French grand opera and has remained the tradition in performances of these operas right up to the present day.

Perhaps the most notable feature of Amor & Psyche’s “soundscape” is the kaleidoscope of musical styles and periods jumbled together in an hour-long program. During the Baroque, modern audiences rarely listened to music from earlier eras. Every court and cathedral had resident composers, and music for all occasions was being cranked out a prodigious rate. Certainly most composers, even the greats like Bach and Handel, “borrowed” from themselves, but with so much new music being written, there was no need to present a cantata by Alessandro Stradella (1639-1682) or songs by John Dowland (1563-1626) for a musical concert in the eighteenth century. Juxtaposing a lute song and a Handel opera aria composed 100+ years apart, like we do several times in Amor & Psyche, is a decidedly un-Baroque feature of the program. It does, however, give the listener the opportunity to relish the differences at close proximity and to marvel at the rich diversity of emotional expression in this music.

If you have any questions or would like more information about the instruments or the voices (or to have Alan demonstrate the difference between his baritone voice and his countertenor voice!) please feel free to stick around and see us after the performance.