Repertoire

The repertoire described here has been successfully road-tested in diverse venues, always receiving great enthusiasm from audience members of all stripes, whether connoisseurs, neophytes, or misanthropes. Each work was conceived and developed collaboratively by members of Opera Feroce, and each production has been designed to have minimal set and production requirements, rendering it suitable for nearly any kind of venue.

Amor & Psyche

A pasticcio opera recounting the timeless tale of love, loss, reconciliation and jealous in-laws!

Amor & Psyche

A pasticcio opera recounting the timeless tale of love, loss, reconciliation and jealous in-laws!

“A successful pastiche opera requires a creative chef to blend disparate ingredients into a satisfying whole, like “Amor & Psyche.””

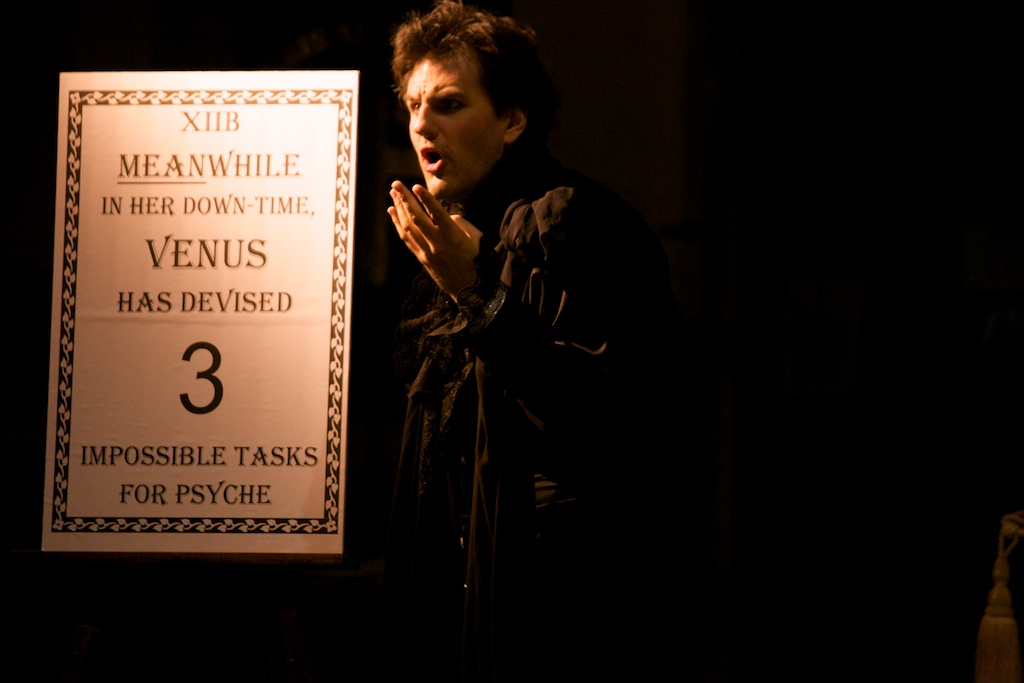

The pasticcio opera Amor & Psyche mixes elements of vaudeville, opera seria, slapstick and tableau vivant into a subtle and witty parody of baroque opera in all its gender-crossing over-the-topness. Drawn from the baroque obsession with Antiquity, the story depicts the myth of Cupid, god of love, and his marriage to the mortal princess Psyche. The piece was constructed by overlaying the music of thirteen composers spanning two hundred years onto the tale. English Lute songs, secular cantatas, as well as Italian and German baroque opera and oratorio have all been plundered in the making of this work.

Vaudeville-style placards denote scene changes and provide additional background and commentary to move the action along and assist audience comprehension. Staged and Costumed.

Forces for Amor & Psyche:

- 3 singers (Amor, Psyche, and Everyone Else)

- chamber ensemble of 3 instrumentalists

Running time:

- 70 minutes of music, intermission optional

Amor & Psyche debuted in August 2010 on the program series “Playthings of the Gods” presented by Vertical Player Repertory.

“… masterfully hodge-podged together into a truly eclectic, trilingual masterpiece.”

“ Even if you don’t love, or even like opera, you will enjoy Amor and Psyche. It is funny, it is touching, and it is thoroughly entertaining.”

+ Program Notes

After a Cliff’s Notes–style introduction of the characters and a somewhat random vocal overture (Lamento di tre amanti), the action begins as we find ourselves in a wooded glen near the palace of Psyche’s father. Psyche (which means “butterfly” in Greek) is a mortal girl whose beauty has caused worshippers to abandon the temples of the goddess Venus and pay homage to her instead, pissing Venus off. Oblivious to the danger she is in, Psyche blithely catches her little namesakes near her home (La Farfalletta).

Spying on Psyche from directly overhead, the irate Venus blows a lot of hot air around, calling on all the forces of nature and her son, Amor, to avenge her against this young upstart (Fire, fire; Furibondo spira il vento). The blood-thirsty Amor, a.k.a. Cupid, a.k.a. the god of love, absolutely lives for this kind of gig and, in a fit of over-achievement, agrees to wreak general havoc on mortals and gods alike. He also agrees to shoot the girl with one of his arrows and cause her to fall in love with a monster (his pièce de résistance) (Volaro, feriro). Instead, things go terribly awry when he is accidentally pricked with the arrow himself and falls madly in love with Psyche (All’armi; Son vinto). Mother and son harmonize with varying degrees of sanguinity about the risks Love runs when plotting the downfall of Innocence (Cosi` va).

In the meantime, Psyche’s father has sought the advice of the Oracle at Delphi regarding what to do about her. His other, far less lovely, daughter has already made a brilliant marriage to a king, but sad, sorry Psyche’s suitors seem stand-offish. Hmmm. The oracle’s prognosis is that Psyche, having displeased a goddess, must be taken to a mountainous crag to await Death. Naturally, this causes some distress to both father and daughter who lament their fate (O Grief; Son nato a sospirar).

Amor has plans of his own and, as soon as he can shake off his mother, he blows in on the Zephyr to carry Psyche off to his palace (more specifically, his boudoir). Somewhere along they way, they get married, so it’s okay J (Lady if you so spite me). Psyche enjoys all the benefits of being married to the god of love, but with one proviso (pay close attention): She is not allowed to look at him (Dormono l’aure estive).

Things go well with the marriage until Psyche’s jealous sister shows up… (Guerra, guerra; Daphne was not so chaste) …and asks questions which Psyche has trouble answering, like, “What does your husband look like?” She plants the terrible seed of doubt in Psyche’s breast which immediately grows to enormous proportions (the seed, that is) (Gelosia; Toss not my soul).

Fearing he might be an awful monster, which he, of course, is not (Editor’s note: quite the opposite, as a matter of fact!), Psyche takes a lamp and decides to check her husband out while he sleeps, with disastrous results (Farfalletta semplicetta (pt.1); Fuggi, parti). Love cannot live where there is no Trust, so he flees. At this critical juncture, our distraught heroine is ready to end it all(Farfalletta semplicetta (pt. 2)).

After an unsuccessful suicide attempt, Psyche is discovered by the demi-god Pan on his way home from a night of carousing. Pan is a lusty sort of half-goat/half-man type who likes a pretty girl as much as the next half-goat/half-man type, and he seeks to cheer her up with a song and a dance. (Der Rheinische Wein tanzt gar zu fein).

Having somewhat won over the listless Psyche, Pan continues to entertain the crowd while our prima donna goes off to perform three impossible labors dreamed up for her by Venus who is still nursing a serious grudge (Coridon in Geldnöten). Although it seems Psyche has managed to complete her assigned tasks, she blows it at the last minute by deciding to try some of Persephone’s Beauty Powder for herself. Not meant for mere mortals, this powder causes her to fall into a deep sleep reminiscent of Shakespeare’s Juliet.

Amor is languishing without Psyche and is searching for her (Idolo del mio core). Fortunately having better political connections than Romeo, he appeals to Jove himself who, touched by Amor’s unwavering devotion and Psyche’s determination to make amends, grants permission for her to join the immortals on Olympus. But first, he comments at length on the situation (Love stood amazed; Amor nel tuo penar).

And so, Amor wipes the sleep from Psyche’s eyes (Awake, sweet love).

They’re really happy (Caro, cara).

Then, in a rollicking trio, Jove, Venus and Pan give their take on it (Away with you self-loving lads).

Everyone has a good laugh. (Laughing Chorus).

+ Musical Selections

- Introduction (instrumental with added commentary) Nicola Porpora (1686 – 1768) * * from the cantata “Odi qual fasto”

- Lamento di tre amanti (terzetto) Antonio Lotti (1667 – 1740) from “Duetti, Terzetti, e Madrigali a Piu` voci”- Venice 1705

- La Farfalletta (aria – Psyche) Francesco Mancini (1672 – 1737) from the cantata “La Farfaletta”

- Fire, Fire (song – Venus) Thomas Campion (1567 – 1620) from “The Third Booke of Ayres” London 1617

- Furibondo spira il vento (aria – Venus) G. F. Handel (1685 – 1759) * * from the opera “Rinaldo”- London 1711

- Volaro

, feriro(aria – Amor) Alessandro Stradella (1639 – 1682) * * from the cantata morale “Otia si tollas periere Cupidinis arcus”- Genova 1680 - All’armi (fragment - terzetto) Stradella (ibid.)

- Son vinto... Cosi` va (duetto – Amor & Venus) Stradella (ibid.)

- O Grief (song – Psyche’s Father) John Coprario (? c. 1570 – 1626) from “Songs of Mourning”- London 1613

- Son nato a sospirar (duetto – Psyche & father) Handel * * from the opera “Giulio Cesare”- London 1724

- Lady if you so spite me (song – Amor) John Dowland (1563 – 1626) from “A Musicall Banquet” 1610

- Dormono l’aure estive (duetto – Amor & Psyche) Francesco Durante (1684 – 1755)

- Guerra, Guerra (fragment – terzetto) Stradella (“Otia...Cupidinis arcus” again)

- Daphne was not so chaste (song – Psyche’s sister) Dowland

- from “The Third and Last Booke of Songs or Aires” London 1602/03

- Gelosia (duetto – Psyche & sister) Pietro Soresina (18th century)

- Toss not my soul (song – Psyche) Dowland from “The Second Booke of Songs or Ayres” London 1600

- Farfalletta semplicetta (aria – Psyche) Giuseppe Savatelli (18th century) from the cantata “Farfaletta semplicetta” (manuscript)

- Fuggi, parti (fragment – terzetto) Stradella (still from “Otia...arcus”)

- Farfaletta semplicetta (continued) Savatelli

- Der Rheinische Wein tanzt gar zu fein (song – Pan) Adam Krieger (1634 – 1666)

- Coridon in Geldnöten (song – Pan) Johann Philipp Krieger (1649 – 1725) from the opera “Flora”

- Idolo del mio core (aria – Amor) Porpora from the cantata “Idolo del mio core”

- Love stood amazed (song – Jove) Dowland from “The Third and Last Booke of Songs or Aires”- London 1602/03

- Amor nel tuo penar (aria – Jove) Handel from the opera “Flavio”- London 1723

- Awake sweet Love (song – Amor) Dowland from “The First Booke of Songes or Ayres”- London 1597

- Caro, cara (duetto – Amor & Psyche) Handel from the opera “Atalanta”- London 1736

- Away with you self-loving lads (song – Jove, Venus & Pan) Dowland from “The First Booke of Songes or Ayres” 1597

- Laughing Chorus (terzetto) Handel from the oratorio “L’Allegro, il Pensieroso ed il Moderato”- London 1740

+ Cast and Production

- Hayden DeWitt (mezzo-soprano) — Amor

- Beth Anne Hatton (soprano) — Psyche

- Alan Dornak (countertenor) — Venus, Pan, Jove, Psyche’s father and sister

- Kelly Savage, harpsichord

- Vita Wallace, violin

- Motomi Igarashi, viola da gamba

“Great performance last night — the singing was excellent and the music selections for the pasticcio were spot on. Enjoyed Alan’s channeling of his inner Charles Busch as Venus and Paul as a guide for the perplexed. But most of all, the lovely ensembles were — ravishing!”

Arminio in Armenia

... a budget epic

Arminio in Armenia

... a budget epic

Arminio in Armenia, Opera Feroce's second pasticcio opera and most ambitious work to date, is an affectionate send-up of Baroque opera – a “faux-pera seria” – created by combining virtuosic music by the Italian composer Nicola Porpora (1686-1768) with a plot conceived by Opera Feroce’s Hayden DeWitt. Porpora was known as the premier voice teacher of his day, having even the great castrato Farinelli as a student; his exciting, dramatically expressive, and wide-ranging vocal writing was the impetus behind this project. Arminio’s scenario pokes fun at common conceits of Porpora’s day: an exotic locale (Massachusetts!), mistaken identity, sorcery, star-crossed lovers, swordplay, and a shipwreck. All music is sung in the (nearly) original Italian, except for the recitatives, which have freshly-written text in English supporting the new story. Staged and Costumed.

Forces for Arminio:

- 3 singers, playing 2 roles each

- 5-piece chamber ensemble (Continuo, Violin I & II, Traverso)

Running time:

- 90 minutes of music with one intermission

Arminio was developed with help from Vertical Player Repertory’s “In the Works” Series, and made its workshop debut in June of 2012 at Christ Church, Brooklyn.

Our 2014 Brooklyn performances are sponsored, in part, by the Greater New York Arts Development Fund of the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, administered by Brooklyn Arts Council (BAC).

“The deep-seated collaboration has so far served this trio well—their voices blend with the ease and depth of an artisanal latte. More striking, however, is the extended ownership that these three singers have over the work…. The smart ones, like Dornak, Hatton and DeWitt … make their own luck.”

+ Program Notes

Arminio began with the music. We had a taste of it in a lovely, yearning cantata aria (Amor & Psyche). Knowing that Porpora had trained many famous castrato singers of his day, we thought this special relationship with singers was worth exploring. It soon became clear that there was a wealth of music suited to us and our storytelling needs, and we had ‘only’ to figure out the tale.

The plot was inspired by common conceits of operas in Porpora’s day. The name itself is based on one of Porpora’s operas, Germanico in Germania, and the story uses other tropes of opera seria — an exotic locale (Massachusetts!) with exotic residents (Pilgrims!), mistaken identity, star-crossed lovers, perceived villains, witchcraft, and swordplay.

To successfully pull off “A Budget Epic,” you need more than 3 characters. So we decided to have 6, with each singer playing two. We had precedent for multiple characters in Amor & Psyche, in which Alan Dornak played 5 different characters. Alan’s challenge for Arminio is playing two characters in different registers — one countertenor, and one baritone.

We sing arias and ensembles in the (mostly) original Italian; recitatives are Porpora’s with new English texts that go with our story.

“Why Porpora?”

Neapolitan composer Nicola Antonio Giacinto Porpora was either born in 1687, 1685, 1670 or 1686 depending on your source materials proving that it was a lot easier to fake your birth certificate in the 17th century than it is today. Although he composed over thirty operas and numerous cantatas, oratorios and instrumental works, Porpora is primarily remembered as a voice teacher, most notably of the great castrato Carlo Broschi (known as il Farinelli.) We are excited to sing his music because hisaffinity for singers is evident in his demanding, yet beautiful, writing for the voice.

He was active in Dresden, Venice, Naples and London, where he and Handel were rivals and where Porpora prevailed thanks to his famous pupil Farinelli for whom he composed his best works. Like any self-respecting genius, he died in an extremely deteriorated physical condition and in abject poverty, either in 1766, 1767 or 1768.

+ Musical Selections

- Chi nel signor confida (Madrigal) Arminio et al

- Saggio nocchier che vede – Arminio

- So che tiranno – Norberto

- Sei mio ben, sei mio Norberto – Tusnelda

- Io ti miro e poi sospiro – Arminio

- Tu mi scherzi, mi burli, m’inganni – Adalberto and Clorofilla

- Quando soffre un cor costante – Genovinda

- Sento che in sen turbato – Tusnelda

- Tradito, sprezzato – Adalberto

- Questo è il valor guerriero – Arminio

- Fuggi dagli occhi miei – Norberto

- Temi lo sdegno mio – Noberto, Tusnelda and Arminio

- Se nell’amico nido – Clorofilla

- Intendi i detti miei – Arminio

- Così perir tu vuoi – Arminio, Adalberto and Clorofilla

- Che cosa t’aggitò – Adalberto and Clorofilla

- Quella ferita che porto in seno – Genovinda

- Fosti il mio ben – Tusnelda

- Su la destra imprimo i baci – Arminio and Tusnelda

- Quella ferita (reprise) – Norberto

- All’amor dei nostri cori – Norberto and Genovinda

- Finale Ultimo - tutti

Sources: Operas: Germanico in Germania, Carlo il Calvo, Semiramide Riconosciuta, and Agrippina Cantatas: “Queste che miri, oh Nice,” Siedi, Amarilli,” and “Oh Dio! Che non e` vero!” Madrigale a 4 voci con strumenti Sonata per violino in G (grave)

+ Characters & Synopsis

- Arminio (Hayden DeWitt): a hero sent by the Pope to convert the Armenians to the One True Faith

- Norberto (Alan Dornak): Governor of Massachusetts

- Adalberto (Alan Dornak): a simple country fellow, identical twin brother of Norberto

- Tusnelda (Beth Anne Hatton): a witch, in unrequited love with Norberto

- Clorofilla (Beth Anne Hatton): a country girl, loved by and in love with Adalberto, but playing hard-to-get

- Genovinda (Hayden DeWitt): a pilgrim girl, in love with Norberto, but without hope of his reciprocating

Rome and Massachusetts Bay Colony in the year 1630

Pope Urban VIII has commissioned the warrior Arminio to lead a crusade to convert the Armenian infidels to Catholicism. (Chi nel Signor confida) After setting sail, a huge storm strikes Arminio’s fleet. He washes up on the shores of Massachusetts, everyone else having perished. (Saggio nocchier)

Enter Norberto, the Governor of Massachusetts. Arminio wonders where the storm has deposited him, since the coast doesn’t appear to be Armenia. No matter the danger, he vows to stay true to his Papal mission. He is informed by Norberto that he (Norberto) is the local governor and that no one is going to be converting anybody on his watch. (So che tiranno io sono)

Exit Norberto. Enter Tusnelda, a sorceress. Arminio is immediately struck by her beauty. She, however, has eyes only for Norberto. (Sei mio ben, sei mio Norberto)

Exit Tusnelda. Arminio exchanges sea-sickness for love-sickness. (Io ti miro, e poi sospiro)

Exit Arminio. Enter Adalberto and Clorofilla, a country couple, playing hide-and-seek. They argue for the umpteenth time about their relationship which consists mostly of his chasing her and her playing hard-to-get. Towards the end of the duet, Clorofilla blind-folds him and runs off. Adalberto gropes his way off after her. (Tu mi scherzi, mi burli, m’inganni)

Enter Genovinda, a pure and wholesome Pilgrim girl toting a sketchpad and a No. 2 quill pen. It turns out her masterpiece is a portrait of Norberto, betraying her hopeless, helpless, hapless infatuation with the Governor. (Quando soffre un cor costante)

Exit Genovinda. Enter Tusnelda who has decided to use her “arcane knowledge” (a code name for “witchcraft”) to prepare a potion to make Norberto fall in love with her, although she realizes that she runs a dangerous risk in doing so, since discovery means certain death. (Sento che in sen turbato)

Exit Tusnelda, freshly-concocted potion in hand. Enter Adalberto, still blind-folded. Realizing that he has been given the slip once again by the perfidious Clorofilla, he gives up the game and comments on his despair. (Tradito, sprezzato)

Enter Tusnelda, relieved to have located her prey in such short order. Thinking she is face-to-face with Norberto, she obsequiously approaches Adalberto. He is confused and comments on this. Noticing the difference in his voice, Tusnelda asks if maybe he has a cold and tells him that she has “just the thing” to fix him up (the potion, of course.)

Enter Arminio. Angry at seeing the two of them together and still vowing to convert the Pilgrims, he challenges “Norberto” to a duel. Tusnelda cuts her losses for the moment and departs as Arminio draws his sword. The panic-stricken Adalberto flees and Arminio laughs at the cowardice of the enemy when faced with the bellic prowess of a Roman soldier. (Questo e` il valor guerriero)

Enter the real Norberto. Seeing that Arminio is still in Massachusetts, he vows to make him leave by brute force, if necessary. (Fuggi dagl’occhi miei)

Arminio and Norberto attempt to dook it out while Tusnelda (who has returned to the scene) wrings her hands from a safe distance until, fearing for Norberto’s life, she decides to intervene. (Temi lo sdegno mio)

Intermission

At the top of Act Two, Clorofilla enters on a laundry-drying mission. She compares herself to the helpless turtledove who, finding the nest empty, flies in search of her beloved mate. In spite of all her bravado, she really does love Adalberto. (Se nell’amico nido)

Enter Adalberto. He has had enough of Clorofilla’s teasing ways and threatens to teach his recalcitrant sweet-heart a thing or two. Clorofilla starts to throw a temper tantrum.

Enter Arminio. Once more he thinks he is face-to-face with Norberto and loses no time in renewing his challenge to a duel. In a short, but heart-felt, arioso and trio, Arminio threatens to kill his adversary, Adalberto quakes in his boots, and Clorofilla states the obvious: that her beloved is about to get his butt kicked. (Nasce da valle, Cosi` perir tu vuoi)

They “fight” and, this time, Arminio wounds Adalberto. Exit Arminio, satisfied that justice has finally been served. Clorofilla comes out of hiding and makes it all better with a few kisses. The lovers reconcile after a little more bickering. (Che cosa t’aggito`)

Genovinda enters on the end of the duet and watches as the couple exits together happily. She comments on her own sad, lonely state. (Quella ferita che porto in seno)

Exit Genovinda. Enter Norberto, angrily dragging Tusnelda who, according to Pilgrim law, must be burnt at the stake for the use of witchcraft. She pleads with him to spare her life, saying she only did it because she loved him, but he remains immovable. Norberto ties her up and exits briefly to procure the means by which to start the blaze. In his absence, Tusnelda remembers her love for him, that love which is now the cause of her death. (Fosti mio ben, fosti il tormento)

Enter Arminio. Having given his best effort to converting the local infidels, he has decided to leave Massachusetts. He sees Tusnelda ready to be executed and vows to save hisbeloved.

Enter Norberto. Arminio threatens to challenge him to another duel, if Norberto refuses to release Tusnelda. He agrees, as long as Arminio takes her back to Italy and they leave immediately. Tusnelda and Arminio sing of their new-found love for each other. (Su la destra imprimo i baci)

Exit Arminio and Tusnelda. Norberto, left alone, comments on his own loneliness. (Quella ferita che porto in seno)

Enter Genovinda. In a tidy turn of events, she reveals her love for Norberto and is delighted to discover that it is reciprocated (but not as delighted as Norberto who had despaired of ever finding a worthy mate among the slim pickings of the colony.) (All’amor de’ nostri cori)

The three happy couples sum things up. (Finale ultimo)

“It was a privilege to hear you — and to see you in your nifty costumes — in Brooklyn Heights last night. We hope to see you again in January.”

Magdalene's Dilemma

Baroque oratorio meets Morality Play

Magdalene's Dilemma

Baroque oratorio meets Morality Play

This intimate staged Morality Play is comprised of excerpts from two Lenten oratorios by Giovanni Bononcini (1670-1747), both of which center around Mary Magdalene caught between Heaven and Earth. The struggle between Sacred and Profane played itself out in the churches, salons and theaters of the Renaissance and Baroque. We bring this argument to life in selections from these works about the Magdalene, symbol par excellence of humankind’s battle to be good in spite of so many compelling reasons to be bad. Lifted out of its original Biblical context, Magdalene’s Dilemma depicts its central figure as an Everyman representing the Soul caught in the struggle between Sacred and Profane Love. Semi-staged and Costumed.

Forces for Magdelene:

- 3 singers (optional narrator)

- 3-piece chamber ensemble

Running Time:

- 40 minutes

This short program can be expanded to full length with the addition of either Benjamin Britten’s A Ceremony of Carols, or a narrator reading sonnets by John Donne, plus additional instrumental pieces.

+ Program Notes

Beth, our soprano and Obscure Music Sleuth extraordinaire, has long been interested in the personage of Mary Magdalene and, while exploring possibilities for a new group project, she chanced upon a number of musical works centering on la Maddalena, as she is called in Italian. In addition, some of these pieces had in common personifications of Divine Love and Profane Love. Since this trio of characters suited the three of us vocally and promised a plethora of entertaining jabs about type casting, we dove in. Two of the source works unearthed by the enterprising Beth were sacred oratorios by Giovanni Bononcini, each written to be performed during Lent, a period when the opera houses were closed and Music Theater moved into the churches along with the public. Bononcini had a long and varied career, sometimes wildly successful, sometimes on the brink of disgrace. The oratorios from which we compiled Magdalene’s Dilemma were written when he was a very young man and already demonstrate the musical characteristics that built his fame – lively, tuneful and agreeable melodies, an uncomplicated and direct expressivity, and a unique and well-developed contrapuntal style, as demonstrated in several of the duets you’ll hear. The Biblical Mary Magdalene has long been at the center of theological controversy and her story has undergone much in the way of manipulation and reinterpretation throughout the centuries. In modern times, she has come to be generally regarded as the most faithful follower of Jesus and, in many scholarly circles, her status as an apostle rivals even that of Peter. In the Seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries, however, she was seen as the penitent prostitute and as a symbol of the transience of pleasure. As such, she is often depicted in Renaissance and Baroque art surrounded by Vanitas symbols like a skull, a burnt-out candle or a mirror. Far removed from any real plot and devoid of Biblical “signposts,” Magdalene’s Dilemma is much less about Mary herself than it is about the human soul’s struggle between flesh and spirit. Any one of us could substitute ourselves for the Magdalene and sit at the center of this little Morality Play where Earthly Love cajoles, tempts and seduces and Heavenly Love takes the time-honored path of the guilt trip. The scenario presents no middle ground and, as such, neither alternative is wholly satisfactory. Caught between two extremes, Maddalena makes a choice, but perhaps not without some regret. There’s no “Happily Ever After,” but it’s okay because that’s not the point here anyway. More than just a musical time capsule, with Magdalene’s Dilemma we have striven to stay true to the purpose of its original sources: to represent a deep spiritual conflict in a direct and unmistakable way. As told through the language of Bononcini’s youthful, light and tune-filled music, perhaps we can easily and good-naturedly catch a glimpse of ourselves reflected in the thoughtfulness and deep humanity of this long-ago depiction of the Magdalene.

+ Musical Selections

Giovanni Bononcini (1670-1747), music from: * La Maddalena a'piedi di Cristo (libretto by L. Forni), Modena, Lent 1690 ** La conversione di Maddalena (libretto by R. Rodiano), Vienna, Emperor's Chapel, Lent 1701

Sinfonia (Adagio - Largo) *

Da quel destino * (Magdalene) Dormi o Cara … Deh, librate amoretti lascivetti* (Earthly Love) La ragione d'un Alma conseglia … Si ridi* (Heavenly Love) E di Costei sia Campidoglio il Core … Vincerò* (Earthly Love, Heavenly Love) Dite voi Geni superni* (Magdalene)

Maddalena, deh siegui* (Earthly Love, Heavenly Love) Voi del Tartaro* (Earthly Love)

Goderò* (Magdalene, Heavenly Love, Earthly Love) Cor imbelle* (Magdalene)

Oh d'un alma che non ha fede* (Heavenly Love) Pensieri che dite* (Magdalene, Heavenly Love, Earthly Love)

Al pentir/vincer/perder mio * (Magdalene, Heavenly Love, Earthly Love)

+ Performers

- Magdalene: Beth Anne Hatton, soprano

- Heavenly Love: Hayden DeWitt, mezzo-soprano

Earthly Love: Alan Dornak, countertenor

Vita Wallace, baroque violin

- Motomi Igarashi, viola da gamba

- Kelly Savage, harpsichord

“Saw it performed today. Marvelous! Marvelous!”

Incontro Barocco

Incontro Barocco

Incontro Barocco is our nod to a salon concert, a kaleidoscope of short solo instrumental and vocal works trespassing across genres, styles and national boundaries. Singers and instrumentalists alike are lavishly costumed in High Baroque style, and the audience is shown more than a glimpse of the 'backstage' relationships, repartee and rivalries among the players. Semi-staged and Costumed.

Forces for Incontro Barocco:

- 3 (or more) singers

- 3 (or more) piece chamber ensemble

Running Time:

- flexible

Incontro Barocco has been presented at Columbia University and Vertical Player Repertory.

+ Program Notes

Incontro Barocco (Baroque Encounter) began as a simple concert, but soon developed a life of its own — like all things Feroce.

Inspired by the model of the baroque salon where overdressed people gathered to eat, drink and listen to overdressed performers, we added period costumes for all performers, and asked the audience to participate as well. We brought food and drink. And in the process of performing, on-stage relationships developed, and the ‘concert’ became a peek into an imaginary circle of friends and rivals, vividly brought to life in song.

+ Program

(AS performed on April 6 & 7, 2013)

Udite amanti Luigi Rossi (1597/8 – 1653) Sig.ri Hatton, Dornak & DeWitt “Listen up, lovers! The Goddess of Love issues today a challenge to mortal combat. Arm yourselves, if you dare.”

Ohimè dov'è il mio ben, romanesca a 2 Claudio Monteverdi (1567 – 1643) Sig.ra Hatton & Sig.? DeWitt “Where is my heart’s true love? Who has taken her from me?” “Only the desire for honor can transform this suffering.” “Over-reaching ambition had more power over me than did my love.” “Cruel, blind world! Because of you I take my life.”

Mi palpita il cor, solo cantata G. F. Händel (1685 – 1759) Sig. Dornak “Ah! I am miserable (and long-winded) because the beautiful, but heartless, Clori doesn’t know I exist. Oh God of Love, if you cause her to suffer as much as I do, I will never cease worshipping at your shrine!”

Sonata in e minor for flute, movement 1, grave Friedrich der Große (1712 – 1786) Sig. Trent Baroque flute players everywhere are eternally grateful to Prussian king Frederick the Great, the Warrior Flutist, an “Enlightened Despot” in the music salon as well as on the battlefield.

The soft complaining Flute, from Ode for St. Cecilia’s Day Händel

Sig.ra Hatton

Nei giorni tuoi felici,from the opera L’Olimpiade Antonio Vivaldi (1678 – 1741) duetto di Megacle e Aristea Sig.ra Barnes & Sig. DeWitt a lovers’ quarrel in 3/8 time

Temi lo sdegno mio, from the opera Arminio in Armenia Nicola Porpora (1686 – 1768) terzetto di Norberto, Arminio e Tusnelda Sig.ri Hatton, Dornak & DeWitt Norberto: “Fear my wrath, oh vile one”! Arminio: “Not on your life!” Tusnelda: “Ah! Ah!” Norberto: “You’ll beg for my mercy!” Arminio: “Never!” Tusnelda: “Ah! Ah!”

INTERMISSION

Sù sù sù pastorelli vezzosi Monteverdi

Sig.ri Hatton, Dornak & DeWitt

a wordy, bucolic offering involving shepherds, birds, fountains, flowers, fields, and a sunrise

La Pastorella lascia la villa, from the solo cantata Freme il mar Porpora

Sig. DeWitt

Continuing in the same pastoral vein as the preceding number, the shepherdess leaves the village to gather roses and the shepherd leaves his flock to follow her. Meanwhile in the avian realm, the turtledove flies the coop in search of its mate.

Sound the Trumpet, from Come Ye, Sons of Art Henry Purcell (1659 – 1695)

Sig.ri Dornak & DeWitt

Vedrò con mio diletto, from the opera Il Giustino Vivaldi aria di Anastasio Sig.ra Barnes “In the company of my beloved, my heart shall be fully content (which is surprising considering the somewhat lugubrious tone of this aria…) But if Fate keeps us apart, I will sigh all my days.”

Non è amor, ne gelosia, from the opera Alcina Händel

terzetto di Alcina, Ruggiero e Bradamante

Sig.ri Hatton, Barnes & Dornak

Ruggiero and Bradamante (husband and wife) are reunited after many misadventures involving attempted seduction, witchcraft, transmogrification and cross-dressing. In this trio, the master-mind behind the plot, Alcina, a sorceress, attempts to make light of the preceding three hours of the opera while the happy couple tell her off.

Sonata in b minor for flute, movement 3, presto Johann Joachim Quantz (1697 – 1773)

Sig. Trent

an offering by the teacher of Frederick the Great

La ragion, se dà legge agli affetti, from Alcide al Bivio Johann Adolph Hasse (1699 – 1783) quartetto di Edonide (ossia il Piacere), Aretea (ossia la Virtù), Alcide, e Fronimo (suo Ajo) Sig.ri Hatton, Barnes, Dornak & DeWitt a tuneful argument for the merits of Temperance and Reason particularly in regards to affairs of the heart

Zefiro torna Monteverdi Sig.ri Hatton & DeWitt the original “Don’t Worry, be Happy”

Gran follia di Pittor Nicolò Fontei (d. 1647 or later) Sig.ri Hatton, Dornak & DeWitt The foolish painter depicts Love as a blind little boy with wings. Love has never ever been blind. He sees far better than you or I! After all, how could he be blind if he hunts such beautiful prey?

+ Performers

- Beth Anne Hatton and Judith Barnes, sopranos

- Hayden DeWitt, mezzo-soprano

- Alan Dornak, countertenor

- Kelly Savage, harpsichord

- Motomi Igarashi, viola da gamba

- Joseph Trent, traverso

Costumed by Deborah Houston.

“ It was a sophisticated evening, the musical learning concealed behind a façade of fun. All we needed to complete the illusion was a Roman feast and a cardinal’s salon in which to perform it, probably not during Lent.”

Treble in Paradise

C-Clef Songs for Gods, Angels and Jilted Lovers

Treble in Paradise

C-Clef Songs for Gods, Angels and Jilted Lovers

Treble in Paradise is a trio-rich program pulling heavily from two of Opera Feroce's favorite composers, 17th Century madman Alessandro Stradella (1639-1682) and Händel's main rival Nicola Porpora (1686-1768), and more.

Season opener of the GEMS Midtown Concerts 2015-2016 season

September 17, 2015 at 1:15m at:

Chapel of St. Bartholomew’s Church

325 Park Avenue at East 50th Street

New York, NY

+ Program

- "Felice, beato chi sa" - trio from L' Oratio (Stradella)

- "Bei ruschelli crisatallini" - trio from Circe (Stradella)

- "Febo son'io...su Camene" - Apollo's aria from Otia Si Tollas Periere Cupidinis Arcus (Stradella)

- "Ed io che farò...nudo arcier - Mars' aria from Otia Si Tollas Periere Cupidinis Arcus (Stradella)

- "Selve amiche...Cupido è la fiera" - Diana's aria from Otia Si Tollas Periere Cupidinis Arcus (Stradella)

- "Mortis causa tu fuisti" - from Six Latin Duets on the Passion of Christ (Porpora)

- "Alla caccia del alme" - solo cantata (Porpora)

- "Sound the Trumpet" - duet (Henry Purcell)

- "Gran Follia di Pittor" - trio (Nicolò Fontei)

A Ceremony of Carols

Benjamin Britten's iconic masterpiece revisited

A Ceremony of Carols

Benjamin Britten's iconic masterpiece revisited

Although Opera Feroce’s focus is generally on the music and forms of the Baroque; we do make the occasional foray into other musical eras. A favorite twentieth-century work is Benjamin Britten’s (1913-1976) A Ceremony of Carols. The original scoring is for treble choir and harp, but we did not let that deter us from tailoring it to our forces consisting of three soloists and harpsichord.

In this magically evocative seasonal work, Britten set a collection of Medieval and Renaissance poems celebrating the birth of Christ and reflecting the veneration of the Virgin Mary. A unique characteristic of Opera Feroce's performance is the inclusion of an actor readings of the original poems. This affords the audience a deeper experience of the poetry and a richer appreciation of Britten’s ingenious text settings.

Forces for A Ceremony of Carols:

- 3 Singers (Soprano, Mezzo-Soprano, Countertenor)

- Harpsichord

- Actor

Candelmas

a sacred and profane celebration for mid-winter with music from four centuries

Candelmas

a sacred and profane celebration for mid-winter with music from four centuries

+ Program Notes

Here is the transcript of a recent interview we never did with NPR.

NPR: Why “Candlemas?” OPERA FEROCE: Funny you should ask. For a while we toyed with calling this program “Groundhog Day” but thought it didn’t have quite the right ring, so we decided to go with the more mellifluous “Candlemas,” instead.

NPR: So, why “Candlemas?” OF: Like Groundhog Day, Candlemas, or The Feast of the Presentation, falls on February 2nd. Unlike Groundhog Day, it marks the fortieth day after the Birth of Christ when, according to Jewish law, Mary would have undergone a rite of purification and presented the infant Jesus in the temple. The famous Canticle of Simeon, the Nunc dimittis, is an eloquent Scriptural marker of this celebration which, for many, signals the end of Christmastide. In fact, superstition has it that, if you haven’t taken down your Christmas decorations by Twelfth Night, you must leave them up until Candlemas. Even though, technically, we missed the cut-off by a couple of days, we figure that this sanctions us to still be singing “A Ceremony of Carols” in February.

NPR: OK, that explains the Sacred, but your program calls itself “A Sacred and Profane Celebration of Mid-winter.” What about the Profane part? OF: You mean besides all the swearing during rehearsals?

NPR: hee hee OF: Well, ever the equal opportunists, we felt that, even though on the one hand, this is our belated Christmas concert, on the other, there is definitely enough Pagan energy afoot, this time of year, for the Profane to deserve equal billing. Let’s face it, if you were to superimpose the Christian calendar onto the ancient Roman one, you’d realize that that’s exactly what the early Christians did. The Romans loved their holidays and had nearly as many feast days as work days in a calendar cycle. Appropriating the already existing public feriae and assigning them to the main Christian feasts could well have been a tactical move to ease the pangs of conversion. Of course, two of the biggest occurred in December: Saturnalia, a carnival-esque celebration with banqueting and gift-giving leading up to the Winter Solstice, and the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti or Birthday of the Unconquerable Sun on December 25th. (Compare that to the Birthday of the Unconquerable Son celebrated by Christendom on the same day!)

NPR: Wow! Your answers sound just like a Wikipedia entry! OF: (insulted sniffing noises)

NPR: That is to say, it seems like you guys have really done your research! OF: Well you know, we are recent inductees into the very elite organization C.U.S.S. (Collegium Universalis Scholarae et Scheisterae), Inwood Chapter. Anyway, as I was saying, Candlemas also coincides with Imbolc, the halfway mark between the Winter Solstice and the Spring Equinox. And on February 1st, Irish Catholics observe St. Brigit’s Day, while various Pagan sects celebrate the feast of Brighid (the Gaelic goddess of the hearth and fecundity) which marks the beginning of Spring.

NPR: And what about Valentine’s Day? I mean, what’s love got to do, got to do with it? OF: The Romans celebrated their fertility rites from February 13th until 15th at Lupercalia, a drunken revel dedicated to Venus which makes modern-day Mardi Gras look like a Junior Prom. This one must have posed a real conundrum for the early Christians, but, luckily, somewhere in the Middle Ages, the day became associated with a 3rd-century Roman martyr named Valentine who had been executed by Emperor Claudius II on February 14th.

NPR: That seems appropriate. After all, who among us has not been a martyr on some Valentine’s Day or another? OF: Too true. Too true. And in honor of such a miserable holiday, we are debuting some new pieces from a blood-thirsty moral cantata by Alessandro Stradella entitled Otia si tollas, periere Cupidinis arcus (a proverb from Ovid which translates roughly to, “We got trouble right here in River City.”) It’s all about the gods devising terrible punishments for Cupid. If you read the text translations (or listen to his bass lines), you’ll probably agree that Stradella must have had some serious anger issues.

NPR: And what about Porpora? He also seems to be featured. OF: Yeah, we Feroces love our Porpora. Not only is his music fun to sing, but he also included trios in his operas, which not a lot of the baroque guys were doing. This probably has something to do with the difficulties, even then, of getting people together to rehearse. Hey, we never have enough rehearsal, but do we let that stop us? We just ply people with food and drink and figure that they’ll be more forgiving that way.

NPR: I notice you are also playing music at the intermission? Does that have anything to do with the eating and drinking you mentioned? Are there any specific instructions for the audience? OF: Imbibe, nosh and frolic! We are dedicated explorers of the baroque ethos, and to us that means eating during performances.

NPR: By the way, is that THE Mark Ettinger, formerly of the juggling troupe The Flying Karamazov Brothers, playing viola da gamba? OF: Indeed it is! Mark is a crazy-talented musician who, after mastering 17 instruments, stopped counting. With some mild coercion, he agreed to dig his gamba out of the back of the closet and join us for these concerts. We feel like he’s a little under-used so, next time, we plan to ask him to juggle a gamba and a cello, while playing the trombone.

NPR: And when did Kelly grow a beard? OF: You must mean Kelly Savage our harpsichordist. She may be sporting some new facial hair, but we wouldn’t know because she lives in California now. She does plan to come back from time to time, but life and Opera Feroce must continue, so we are extremely fortunate to be joined by Gabe Shuford, pianist, harpsichordist and jazz god. All the guy needs is a better instrument to play, but we’re working on it.

NPR: Speaking of which, did I hear that Opera Feroce is looking for a harpsichord? OF: Yes, specifically a small, light-weight, loud, cheap or free, high-quality single-manual Flemish or Italian instrument with two eights and a lute stop.

NPR: Anything else to add, as this interview limps to a close? OF: I’d like to say a brief word about the Giovanni Pacini selection at the end of the program. There was some concern that it might obliterate all of the other music on the concert, and it is loud, but it is also neat, especially given that the last live performance on record of any portion of this opera was in 1845! Here is a brief synopsis of I Fidanzatiprovided by Thea Cook, a historian of bel canto opera who approached us with the score after seeing a performance of our opera Arminio in Armenia and realizing that we would probably be intrepid enough to attempt to produce it (and we just might be…): The opera is based on Sir Walter Scott’s novel The Betrothed, and follows the ill-starred love of Evelina (Beth) and Damiano (Hayden), whose father Ugo de Lacy (Alan) was promised to Evelina by her dying father. When Ugo is ordered by King Richard to join the crusades, he leaves Evelina in Damiano’s care. The young lovers fight their passion, and though eventually they confess their feelings, they do not act upon them. Ugo discovers their feelings for one another upon his return, but after initially repudiating his son, at the last moment he places Evelina’s hand in Damiano’s, relinquishing his claim on her, and the opera ends in general rejoicing.

+ Musical Selections

- Duetto per flauto e violino, Wq 140 C.P.E. Bach (1714 -1788) andante

- A Hymn to the Virgin Benjamin Britten (1913 -1976)(Anonymous, 14th century)

- A Ceremony of Carols Britten

music at the intermission

Duet in G major for flute and violin, TWV 40:111 Georg Philipp Telemann (1681-1767) (from Der getreuer Musikmeister)

- dolce

- scherzando

- largo e misurato

- vivace e staccato

Opening trio from the operetta à 3 Alessandro Stradella (1639 -1682) La Circe “Bei ruscelli cristallini” (Algido, Zeffiro e l’Ombra di Circe)

3 Arias from the cantata morale Stradella Otia si tollas, periere Cupidinis Arcus

- “Febo son’ io...Sù Camene, al suono, al canto” (Apollo)

- “Ed io che farò...Nudo arcier che ti pregi di forza” (Mars)

- “Selve amiche...Cupido è la fiera” (Diana)

Duetto per flauto e violino, Wq 140 C.P.E. Bach allegro

Duet from the sacred cantata Nicola Porpora (1686 - 1768) Deos qui salvasti

- “Gaude o peccator, plaude o peccator” (Misericordia e Giustizia)

Trio from Act 3 of the opera Porpora Temistocle

- “Vo’ costante in faccia a morte” (Temistocle, Neocle ed Aspasia)

Trio Finale from Act 1 of the opera Giovanni Pacini (1796 -1867) Il Contestabile di Chester ossia I Fidanzati

- Ah, partir...Ver’ la terra del deserto” (Ugo, Evelina e Damiano)

+ Performers

- Beth Anne Hatton, soprano

- Hayden DeWitt, mezzo-soprano

- Alan Dornak, countertenor

- Gabriel Shuford, harpsichord

- Mark Ettinger, viola da gamba

- Joseph Trent, traverso

- Vita Wallace, violin

- Deborah Houston, reader